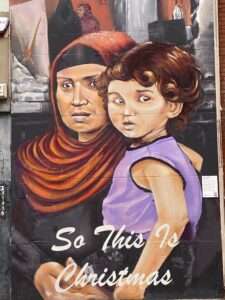

“So this is Christmas?”

So what is Christmas?

The frantic piling of unnecessary items into supermarket trolleys, the frenetic activity in the streets, the frenzied buying as if no shops would be open for days to come? Is this Christmas?

Has any of it anything to do with the birth of a child in an obscure corner of Palestine?

Of course not.

The celebrations are rooted in something far more visceral than the thought of divinity becoming incarnate. There is a human instinct to celebrate at triumph over adversity; the days are turning, the winter will pass, we have survived and the year ahead will offer opportunities as yet unknown. The undercurrent of sexuality among the Christmas revels reflects the instinct to survive, to continue the line, to have a presence in the future. Look at the history of the pagan midwinter festivals and what might be encountered on the streets of any city is not so far removed from the past: look at Saturnalia, at Yule, at the numerous festivities that marked midwinter and what now takes place may seem mild.

No, this is not Christmas, but what is Christmas?

The people in their Christmas jumpers, the friends exchanging gifts in a cafe, the shoppers with multiple carrier bags, these are not people celebrating Christmas, in any religious sense of that word, but what is Christmas?

There are times when it would be more honest for the church to take its celebration and move it to some date in the year where it did not disappear under a pile of presents and countless bottles of drink, but perhaps there is no cause to be unduly concerned. The early church did not celebrate Christmas at all, its introduction into the Christian calendar only coming in later centuries when the church sought to supplant the pagan celebrations with a feast of its own.

And if the presence of Jesus of Nazareth is not acknowledged in most of what takes place, he is probably relieved. Would he have wanted to be associated with excess and drunkenness?

It is not as though many people noticed his presence when he was born – bachelor farmers down from the hills, unwashed, unkempt; a group of foreigners who would probably have problems getting through immigration – hardly an impressive list.

People did not welcome him, “he came unto his own and his own received him not”, as Saint John puts it in the King James Version of the Bible. Bethlehem and Nazareth and Jerusalem were probably as rough as any city on the days before Christmas.

So this is, Christmas.