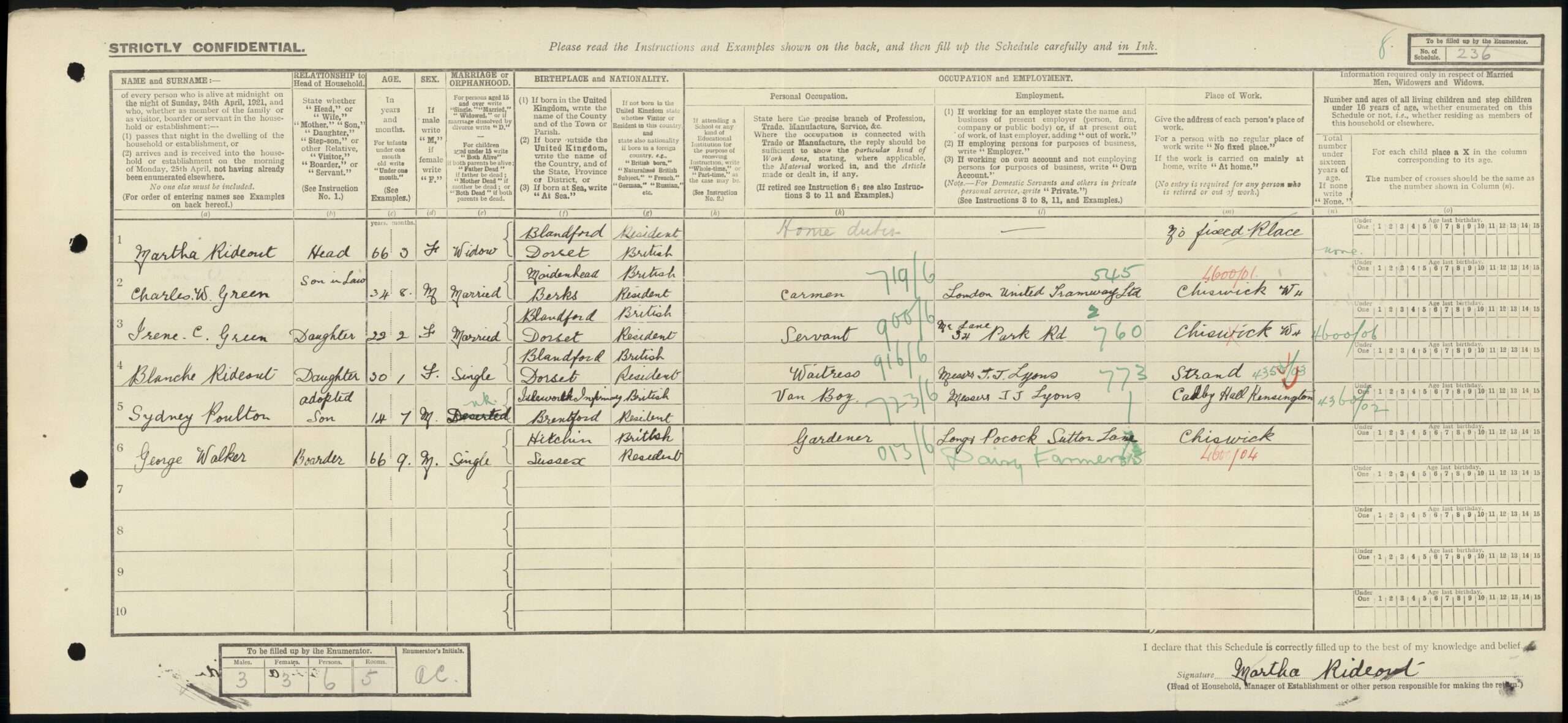

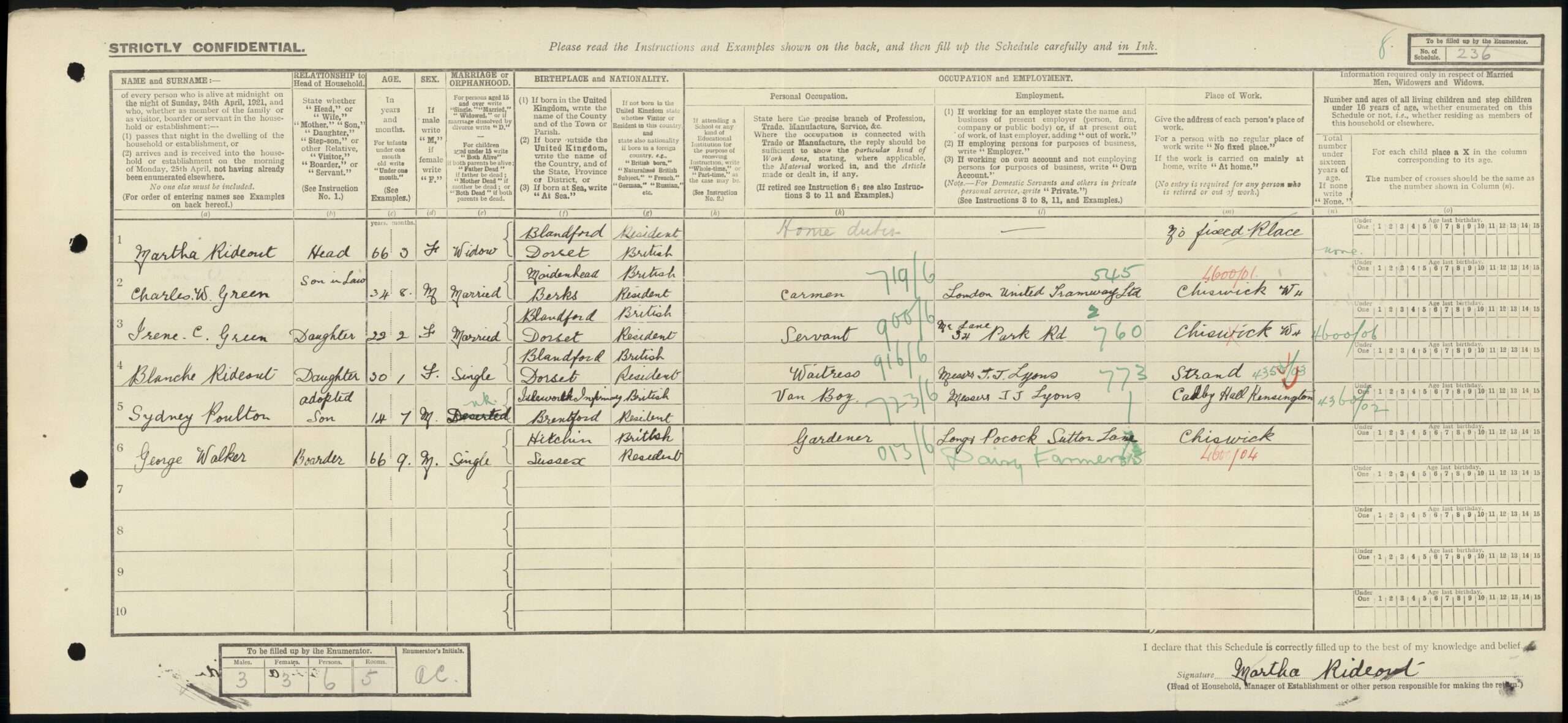

The 1921 Census revealed the whereabouts of my late grandfather. He was living at 38 Holly Road, Chiswick in the house of Arundel Martha Rideout. Mrs Rideout, twice widowed, had entered my grandfather’s name as “Sydney Poulton,” had put “deserted” against his name, and had described him as “Adopted son.”

The census enumerator must have questioned the term “deserted,” for he has put a green pencil line through it and written, “NK,” presumably “not known.”

The return offers no further clues as to who his father may have been, nor any suggestion as to how he came to be living with a family who were entirely unconnected to him. Nor does it offer any explanation as to why he had a kippah, something my grandmother kept even after my grandfather’s death in 1972.

Being Jewish comes through the mother’s line, and her background as Church of England is clearly documented, but could his father have been Jewish?

After the death of their mother in March 1912, his three siblings, or perhaps they were half-siblings, were sent to a Poor Law School in Hampshire, that he was not with them suggests he was being cared for by a family somewhere.

His upbringing seems to have been affluent at times. He had postcards of himself and friends printed when he was eighteen. He is well-dressed in the various snaps of him on outings.

In the 1921 Census, he is shown, correctly as fourteen years and seven months old. His place of birth is shown as that which is shown on his birth certificate, “Isleworth Infirmary.” It was the infirmary for Brentford Workhouse.

Interestingly, Blanche, Martha Rideout’s youngest daughter, and my grandfather are both working for Lyons. It seems a matter of pride for Martha Rideout for she has put Messrs J.J Lyons. Blanche is a waitress in the Lyons Corner House on the Strand (a role that would later come to be described as a “nippy”). My grandfather is a van boy, working from the Lyons factory at Cadby Hall in Kensington.

Perhaps the Lyons connection offers some clue to the kippah? Only when I searched for Cadby Hall did I discover the company had been Jewish. Had his father been among the staff there?

The London Remembers website provides a history of the family and the factory:

The Gluckstein family arrived in London in 1843-7, bringing their trade of selling tobacco with them, and settled in the East End.

In partnership with Joseph Lyons they opened their first Lyons teashop at 213 Piccadilly in 1894. {This was part of the site 212-214 Piccadilly; 21a, 22 and 23 Jermyn Street; and 3-4 Eagle Place; developed c.2015 and now occupied by a building clad in, mainly, white ceramic}. More Lyons tea shops were opened and it became the first respectable chain of restaurants, selling consistent food at consistent prices, catering especially to women who had not previously been addressed. No alcohol was available, food was served by women in maids’ uniforms and there were women-only areas.

In 1894 Lyons acquired Cadby Hall, an old piano workshop, which they turned into their factory producing standardised, consistent products for their restaurants. There they had their bakery, offices, stores, and could manage the delivery to the shops, each run by a family member. Cadby Hall went on to be developed and was soon baking products for sale over the counter, and to restaurants run by others.

In 1896 they built the Trocadero at Piccadilly, a restaurant and bar complex.

Around 1900 the Glucksteins were said to be the largest retail tobacconists in the world and in 1902 they sold that side of their business to Imperial Tobacco. This enabled the members of the family (the Glucksteins and the Salmons) still living in Whitechapel to move out and they settled in West Hampstead, Kensington and Hammersmith.

The first Lyons Corner House was on the north-west corner of Coventry Street and Rupert Street and opened 1909. The second was in the Strand between Charing Cross Station and Trafalgar Square, now demolished. The Oxford Corner House was built 1926-7 to the design of F. J. Wills. It has 3 elevations: one on Hanway Street (of no interest) and two splendid frontages at 14-28 Oxford Street and 3, Tottenham Court Road. When they decided to move into hotels they built the Strand Palace Hotel (opened Sept 1909). In 1911 they opened a large factory in Greenford and also helped fund a new synagogue, the Liberal Jewish Synagogue, {in Hill Street W1 during WWI, it moved to St John’s Wood Road, into an old chapel, in 1925}.

At the end of WW1, to ensure they could continue to innovate with food products, they created a large, modern, food laboratory at Cadby Hall (where, between WW2 and her marriage, Margaret Thatcher worked as a chemist). This enabled them to develop a new product for them, ice cream, which was manufactured at Cadby Hall. Lyons were the sole caterer at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, where they ran over 100 restaurants, bars, etc. 1924 Lyons registered ‘Nippy’ (the term used for their waitresses) as a trademark.

By the Depression of the thirties there were over 60 Lyons restaurants all over England. Lyons was the official baker to the royal family and catered for the Buckingham Palace garden parties. By the start of WW2 they were described as the largest restaurant business in the world.

In 1938 some senior female members of the family converted a building in Kentish Town which had been a Lyons tea shop into ‘The Haven’. This housed 23 children, members of the Kindertransport, which the women collected from Liverpool Street station.

Based on their tremendous organisation skills Lyons were asked to manufacture bombs for the war effort, and in response they built and ran a factory at Elstow which, by the end of the war had supplied one seventh of the bombs dropped on Germany.